Ground Truth in Zurich

And believe it or not, soon after returning from Cyprus I had to go to Zurich. This was to attend a meeting of the European ‘Future Emerging Technologies’ project called IMMERSENCE. The timing was fortunate since my wife also had to give a seminar in Zurich on the same day (yes, she is a scientist). The project mainly consists of experts in ‘haptics’. Haptics is concerned with touch and kinesthetics including force-feedback. Normally of course if you are in a virtual reality and you touch a virtual object you don’t feel it (because nothing is there). Remember that the stereo and head-tracking system may give you the illusion that an object is there right in front of you, but reach out to it, and you will feel nothing. This can (at least temporarily) break presence. Haptics typically employs devices that give back some feeling – normally the force feedback you get on touching something (i.e., when your hand collides with a solid object it does not pass through it) but less often the associated tactile sensation.

And believe it or not, soon after returning from Cyprus I had to go to Zurich. This was to attend a meeting of the European ‘Future Emerging Technologies’ project called IMMERSENCE. The timing was fortunate since my wife also had to give a seminar in Zurich on the same day (yes, she is a scientist). The project mainly consists of experts in ‘haptics’. Haptics is concerned with touch and kinesthetics including force-feedback. Normally of course if you are in a virtual reality and you touch a virtual object you don’t feel it (because nothing is there). Remember that the stereo and head-tracking system may give you the illusion that an object is there right in front of you, but reach out to it, and you will feel nothing. This can (at least temporarily) break presence. Haptics typically employs devices that give back some feeling – normally the force feedback you get on touching something (i.e., when your hand collides with a solid object it does not pass through it) but less often the associated tactile sensation.

My role in the project is to investigate the extent to which presence is induced in a number of paradigmatic application scenarios. In this I work with the researcher Andreas Brogni in the group at Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya in Barcelona.

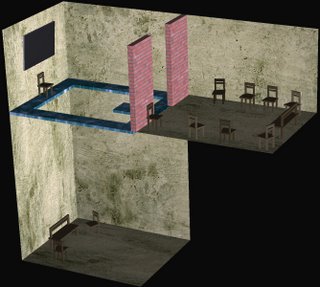

The idea we follow in this project is to compare responses in physical reality to those in virtual reality. For example, if in physical reality you pick up a cup, you will have applied forces, used your hand and arm in a particular way, felt various tactile sensations, resisted against the weight, and so on, all the way through to having various thoughts and feelings associated with lifting that cup. Now when you carry out the same task in a virtual reality, to what extent do you carry out the same actions, and have the same overall responses to your own actions and to the totality of the event ‘picking up the cup’. Presence in the virtual environment is the extent to which your responses are the same as those in the real environment.

Let’s consider this approach to presence a bit more. It is very practical. Ontological considerations can be avoided. But … many people have said that it does not take into account the beauty of virtual reality which is able to create experiences that are not real. For example, in virtual reality you can ‘fly’, there is no naturally occurring virtual gravity that will hold you at virtual ground level. It is all a matter of what the program allows you to do. For example, it is trivial to program the system such that if you look upwards and press a button on the wand (6 degree of freedom ‘mouse’) that you will typically be holding, then you can fly up in the virtual world. And why not? So can we not talk about presence in unreal situations, but only in relation to simulations of physical reality?

There are two answers to this. The first is that if in simulations that are bound to physical reality we learn how to increase the probability that the participant will respond to virtual events and objects as if they were real, then of course we can apply the same knowledge to non-physically grounded simulations, and increase the chance that people will respond to those types of situations and events as if they were real.

But the real answer is that this approach to presence does not demand at all that the virtual environment depict something that could be real – it is only that the responses to the virtual environment should be real (high presence). In other words if you learn to fly within a virtual reality and you respond to that experience as if what you were doing were real, then that is …. presence. Of course, in such situations the hard part is that there is no ground truth against which to compare – we do not usually fly within physical reality (the plane flies, we are just along for the ride). But what we do in virtual reality is expand the range of experience, to know something about what it would be like to fly - with realistic responses helped along by the exploitation of knowledge we have obtained by studying situations in which there is a ground truth.

Then almost immediately after returning from California I had to go to Cyprus (Limassol) for a conference called ‘Virtual Reality Sofware and Technology’ (

Then almost immediately after returning from California I had to go to Cyprus (Limassol) for a conference called ‘Virtual Reality Sofware and Technology’ ( Presence as far as I’m concerned is quite uninteresting if it is limited simply to what people will tell you about their experience after the event – no matter how well ‘validated’ the questionnaire; and you can’t ask them during the event because that in itself could destroy the experience. So presence is to do with how people respond to events and correspondingly how they are able to act within a virtual reality (or even in a mixed reality) – it is their response and activity in relation to virtual sensory data (how exactly it is produced is not important – but if you want to think of it as computer generated on computer controlled displays that is fine).

Presence as far as I’m concerned is quite uninteresting if it is limited simply to what people will tell you about their experience after the event – no matter how well ‘validated’ the questionnaire; and you can’t ask them during the event because that in itself could destroy the experience. So presence is to do with how people respond to events and correspondingly how they are able to act within a virtual reality (or even in a mixed reality) – it is their response and activity in relation to virtual sensory data (how exactly it is produced is not important – but if you want to think of it as computer generated on computer controlled displays that is fine).